|

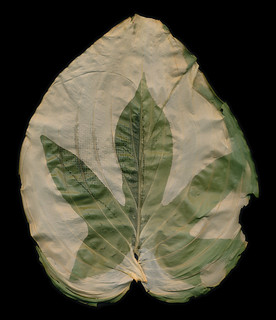

| Sweet Potato Vine leaf imprinted on a Hosta Leaf |

Chlorophyll printing is a cool, fun process. It actually tends to be pretty fast for an anthotype process; it prints in just a few hours if you use the right kind of leaf. If you use the wrong kind of leaf, it can take days and hardly show up at all. So far I've only tried a few kinds of leaves and my best results are from big, thin leaves like hosta and caladium. Thicker, fuzzier leaves don't tend to fade as well. It can record detail very nicely. I've been able to see some pretty decent tonal range in the leaf prints, but the results are more dramatic with strong contrast and easily identified shapes. If your negative relies heavily on subtle textures and delicate shading, it probably won't return a great result. You are, after all, not dealing with a traditional photo-sensitive metal salt process.

Chlorophyll prints are something I plan to experiment with further. I really like Danh's idea of using multiple blades of grass together as a mat to create a large area for exposure. He preserves his chlorophyll prints by casting them in clear resin. I have no idea how that would affect fading, since the resin is still transparent. Then again, I have no idea how archival the chlorophyll prints are in the first place. Dried leaves can keep their color for a fairly long time, after all.

As a final note: I am almost certain this process won't work on evergreen foliage or on autumn leaves or already-dead leaves that have lost all their green. I'm pretty sure the chlorophyll needs to be intact to make this type of print work. Who knows, this fall might prove me wrong!

No comments:

Post a Comment