|

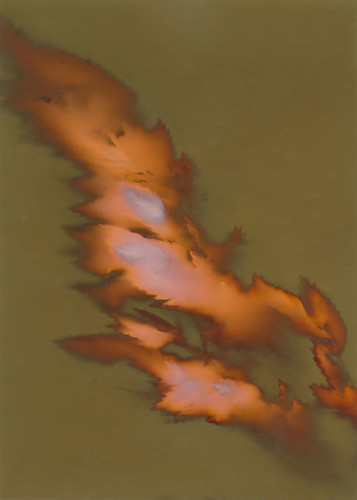

| Unfixed Salt Print on Fotokemika Varycon |

Well, as I've been forced to hear repeatedly in recent days, all you can do once you've made a mistake is learn from it and move on, trying your best not to repeat the mistake. I know that I'll be late to blog again, but I'm really trying to get better. I might even try to write my blogs early and schedule them to automatically post on Thursdays. That'd be pretty novel!

Let's skip that stuff and get to what you actually care about, right? Spiders care nothing for human trials, but love some photography. Or something. Today's topic is one of my recent experiments: salted lumen prints. I was lead to this idea by John Fobes, who coated one of his lumen prints in albumen mixed with ammonium chloride. Mr. Fobes got some very interesting color shifts as a result of printing on the still-wet albumen-coated paper, but it got me wondering if it would be possible to use silver gelatin paper as a base for salt prints to combine the salt print with a lumen print.

I soaked two sheets of Fotokemika Varycon fiber-base paper in a simple solution of filtered tap water and kosher salt, the same kind of solution I'd use to soak normal paper before making a salt print. I used quite a lot of salt, getting the water up to the saturation point. Then, I allowed both sheets to dry completely overnight before coating one sheet in the same 15% silver nitrate solution used for salt prints. I allowed that sheet to dry for several hours as well, then exposed them both as I would normal lumens, for 1 hour each.

Overall, I did not see a big difference between a salt-soaked lumen print and a regular lumen print, at least not on the Fotokemika Varycon paper. They look about the same, the only significant difference being that the salted print had less color and was overall less vibrant. I'll be testing other brands of paper to see if I can achieve different results. I think Mr. Fobes' use of albumen also contributed to the color shifts he saw, not just the application of chloride.

Using the silver gelatin paper as a base for a salt print proved effective. The paper doesn't take coating as evenly as something more porous would, but I think that can be solved with multiple coats of silver nitrate, or just more careful application. The image looks very similar to a traditional salt print, but carries strong undertones of the paper color. The unfixed image carries much more of these tones, but that's because fixing destroys most of the color in Varycon paper. I plan to experiment with a more vibrantly colored paper, maybe Collodio POP or Harman Direct Positive, but the concept proved itself. You can make a salt print on silver gelatin paper, and doing so does affect the final image.